Per Tengstrand: Beethoven’s aim for freedom makes him timeless

Sydsvenskan March 10, 2023 09:00 By Håkan Engström

”I know of no other composer who can affect you so physically, whose music can fill your lungs with air” says the pianist, who has made a film about Beethoven and the student revolt in Hungary 1956.

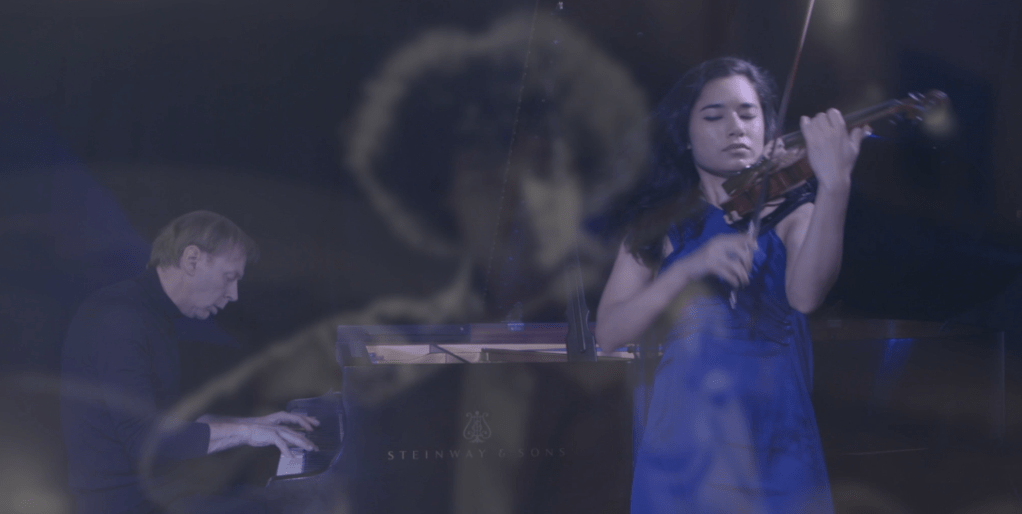

In “Freedom of the Will”, his film debut, pianist Per Tengstrand examines Beethoven’s political explosiveness. Picture: Hussein El-alawi

Håkan Engström is a music editor and writer on the culture page.

The concert pianist Per Tengstrand is one of our most prominent Beethoven interpreters. When the pandemic closed the concert halls, he turned to a new format to portray the great composer: film. “Freedom of the will” tells about how the freedom-loving and proud composer influenced people long after his death.

In special focus is the attempted revolution in Hungary in 1956, when students and others rose up to get rid of the yoke of dictatorship and dependence on the Soviet occupying power. Beethoven’s “Egmont ouverture” gained great symbolic value, since it began to be played by students who occupied the radio house.

The film may be set in Hungary and 1956, but the message is bigger and more timeless than that; the film tells about the quest for freedom and about Beethoven’s ability to speak to us. His music has been used and abused over the years by people with very different agendas. Tengstrand focuses on his humanism, his anchoring in the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and, most of all, on the freedom struggle. Why does Beethoven’s music speak so strongly about this?

– He suffered so many personal tragedies, says Per Tengstrand. This forced a choice: he could give up or he could make sure he had the strength. No one gave this to him, not even God, the strength was created by nobody but himself. This is actually the greatest freedom of all, that you control your own destiny — nothing is predetermined.

It is easy to be fooled by the noble sounding name, but Ludwig van Beethoven came from simple circumstances: a class traveler, self made man, who acquired social status and socialized with the aristocracy.

– He was a bit vane on that issue. If people thought he was from the nobility, he didn’t correct them. But he was still principled about that his life’s work was what defined him.

The filmmaker tells the story with music but also with interviews with aging students who were there in 1956.

– It was pure luck that I got hold of them. I was in contact with Béla Liptak, who had been a leader of the movement and had written books about it. He did not want to be interviewed, because he knew nothing about music. But he forwarded my request to a network of Hungarians who were “fiftysixers”. The next morning my inbox was full of e-mails from people who were ready to tell their stories and also to help me find people who could.

The strongest is probably Éva Aradi’s story, with parallels to Egmont in the late 18th-century play by Goethe that forms the basis of the overture. “Egmont” takes place in 1566 in the Spanish-occupied Brussels, and is a story of rebellion and heroism. Like Egmont, Éva Aradi is thrown into prison.

– Her story still touches me, the way she talks about how she was only 18 and had not yet been in love. And now she thought she was going to be executed. She has an incredible integrity in her storytelling, it is free from sentimentality. She is serious, but never cold.

Goethe’s epic had less to do with 16th-century Brussels than with current conflicts. Completely in line with this, ideologues over the decades have placed their mantle on “Egmont” – and on Beethoven.

In “Beethoven – The Useful Titan” (Gidlunds förlag, 2021), a book about how the composer was retrospectively used for political purposes, author Åke Holmquist describes how communists in the 1920s claimed that Egmont fought for the workers against capitalism and imperialism, while for the Nazis he was a role model who were prepared to die for the Reich. Liberals, on the other hand, saw a democratically minded freedom fighter.

Beethoven’s music has the power, so whoever can use it makes sure to do so.

– You can always try to use him for your propaganda motives, but did it really land in the minds of the people? asks Per Tengstrand. The Hungarian revolt was different: young revolutionaries played a gramophone record in a radio house, and it caused a sensation among ordinary people.

Could another piece have had the same impact?

– That it became that piece was a coincidence, but it has sections that are really strengtening in spirit and very direct. I find it hard to imagine that a more delicate movement from a string quartet would have had the same effect. In the overture there is pride and desire for freedom. It is a power that Beethoven often has, that you can feel the energy in your body and mind.

But of course there are other Beethoven pieces with political explosives.

– Lenin loved the “Appassionata”. He is said to have exclaimed”If the people get to hear this music, we wouldn’t be able to control them anymore”.

Another quote is more recent, it comes from Tengstrand’s film and is pronounced by the composer and author Jan Swafford: “Beethoven wrote for humanity. Mozart wrote for people”.

– It makes you reflect and think. Mozart had no idea when he wrote his piano concertos that they would be played and loved in 2023; it was music he expected to be heard then and there. Beethoven was the first with a view that he was writing music for humanity for all time to come. It gives the music a certain spirit .

Where did this spirit come from?

– From the fact that he valued himself so highly. The common perception towards the end of his life was that he wrote music that couldn’t be played – he was isolated, deaf and a little crazy – the public loved the Appassionata and the Fifth Symphony and the Moonlight Sonata. He didn’t really care if people of his time understood him, but was certain that the time would come when his music got his due.

It indicates strong self-esteem.

– For sure, he was very self confident. He already was in his youth. It takes a lot of confidence if you, as a young composer, say that you are Mozart’s successor!